Regretably, little of James Hanley's work is currently available outside the better

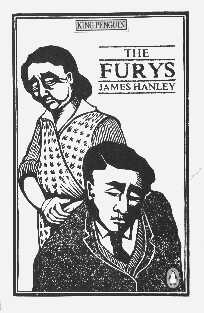

academic libraries and secondhand bookshops, although both The Furys

and Boy have been published as Penguin Modern Classics relatively recently, and copies are still occasionally to be found.

Two titles have so far been published: a group of early novellas under the title

The Last Voyage and Other Stories in late 1997, and more recently the

1941 novel The Ocean.

Copies of both books are still occasionally available in better bookshops on both sides of the Atlantic,

and hopefully more titles will eventually follow.

On a more positive note, Collins-Harvill have recently started to publish excellent softback versions of Hanley's writing. For more information visit their own Web Site at

The Harvill Press.

of The Furys.

There is also news that a new British publisher, House of Stratus, is planning to re-issue many

of Hanley's out-of-print titles, and more information is available from their Website ~

The House of Stratus ~

whilst John Fordham's excellent recent critical analysis James Hanley - Modernism and the Working Class

was finally published by the prestigious University of Wales Press at the end of 2002, and represents the first major

overview of Hanley's work in a generation. No reviews have yet been published.

It's good news indeed that Harvill have recently re-published The Ocean, one of James Hanley's finest novels, in a high quality softback edition, with a fine cover picture by Hanley's son - Liam Hanley. The Ocean was written in the early part of the war, when Hanley was living in London during the worst of the Blitz, and at a time when all writers were struggling to get anything published at all because of war time limitations on paper, and the firm hand of government to prevent anything but the most positive of propaganda appearing. This was a game well suited to Hanley's sense of anarchy, and he actually managed to get four novels and a book of short stories published during the war. As a result The Ocean is a much shorter, much tighter, much more compressed book than much of Hanley's earlier fiction. Originally published in April 1941, and drawing heavily on Hanley's experience at sea during the First World War, it was highly topical at a time when the Battle of the Atlantic was reaching its height, with savage submarine attacks on British shipping threatening to cut the life blood of both military and civilian supplies from the United States.

The plot is simply told. A small passenger ship crossing to Canada is torpedoed at midnight and sinks quickly. All is chaos and confusion in the cold darkness, but some of the lifeboats get away, although not before they are machined gunned by the surfaced submarine. Then all is darkness again. At day break one lifeboat drifts alone amidst a grey empty ocean, containing just four passengers and the elderly seaman, Michael Curtain. The body of another seaman lies dead in the bottom of the boat. The novel is the story of these five men, one a teacher and one a priest, and their struggle for survival in the long days and nights that lie ahead. In fact there is no evidence to support the widespread belief that German U-Boat crews machine gunned survivors of their attacks, and its inclusion at the beginning of the story is an example of the way Hanley was able to respond for the national need for such propaganda. That apart, the theme of survival is particularly appropriate for a nation struggling for its own existence in a largely friendless world, so the novel can also be seen as a metaphor for that larger struggle, although it is only incidentally concerned with the war itself.

Structurally The Ocean resembles Stephen Crane's ‘The Open Boat' (1897), one of the classic accounts of survival at sea written from personal experience. And although Hanley was never shipwrecked himself, he sailed with men who were, and his account is grimly realistic. More importantly, however, is the way Hanley structures Michael Curtain's interior monologue, as he struggles to use his long experience to sustain his disparate group of fellow survivors. A narrative which is constantly cut through by the individual preoccupations of these other men; their fragmented memories, dreams and hallucinations. The climax of the story occurs when a whale surfaces near the lifeboat, with the very different way each man responds. Hanley uses this inspiring natural occurrence as a unifying focus for the rapidly disintegrating group of survivors, subtly indicating that human emancipation and sustainability is to be found in nature rather than the tortured confines of contemporary society, in which war and class remain the defining features.

At the end of the story, the viewpoint shifts from the sailor Curtain to that of the elderly priest, Father Michaels, who has barely survived the ordeal. As the boat nears shore at last he has a vision of a man standing alone on a rock, a vision he takes to be that of Christ Himself; and although this finally dissolves into the physical figure of a fisherman and his boat, it is not sufficient to displace the religious mysticism of the whole experience. So Hanley brings his tale to an end, but it is more in the telling than in the story itself that the novel breaks new ground, and can usefully be paired with another of Hanley's wartime books Sailor's Song (1943), in which a similar theme of survival at sea, is examined through the political and social history of the seaman, as an example of working class struggle and endurance. Hopefully Harvill might soon re-issue this book too, which like The Ocean has also been much too long out of print. Both were books that Hanley's friend John Cowper Powys rated highly, and with good reason, for they are not to be missed by anyone interested in literature that seeks to push back the boundaries of structure in an attempt to find new forms and new expressions. With its subtle intermixture of modernism and realism, this is art of a very high order indeed.